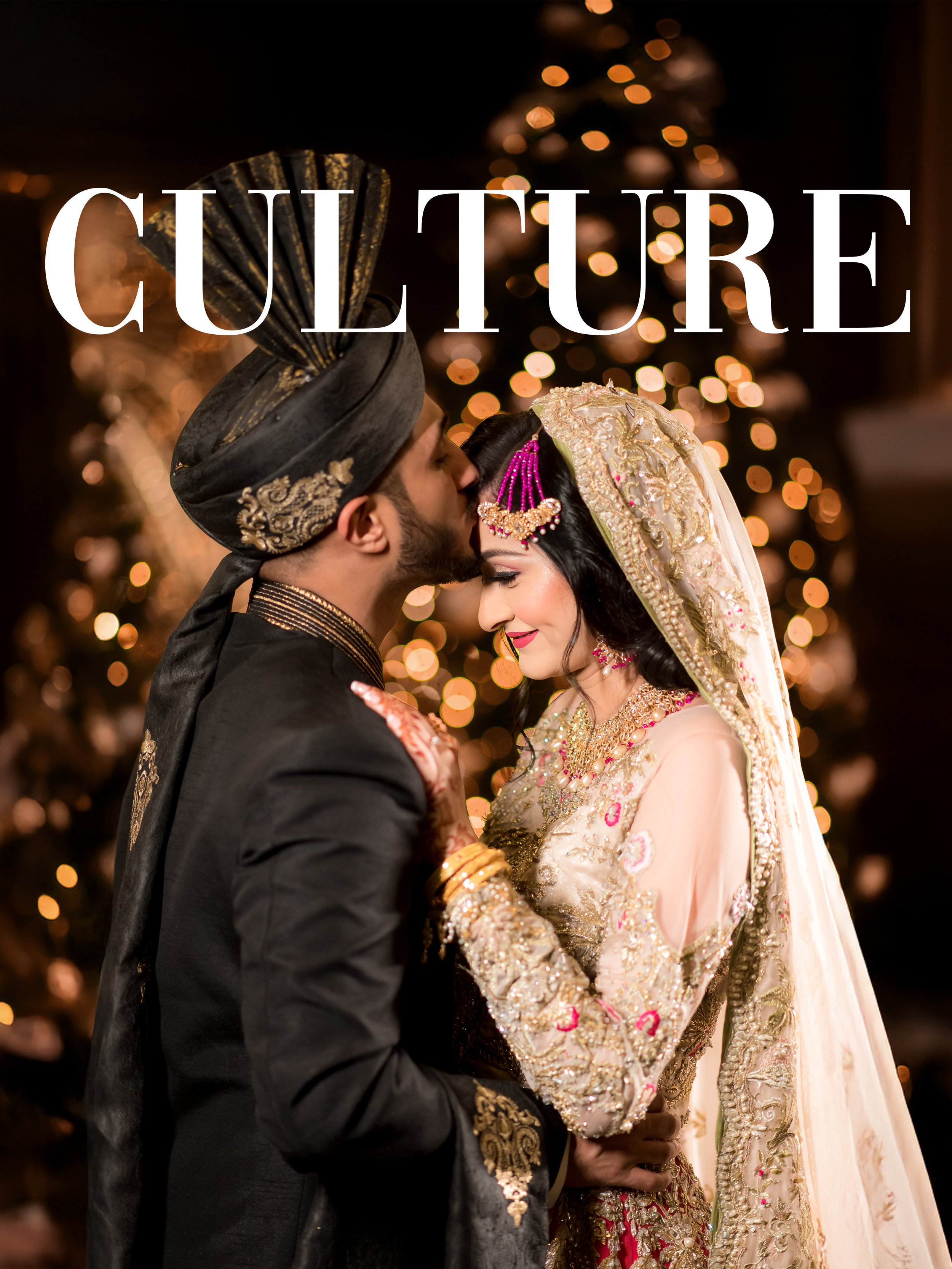

Haldi in Harrow, Jago in Birmingham: How South Asian Pre-Wedding Traditions Change in the UK—and How We Capture Them

A haldi ceremony in Harrow looks nothing like a haldi in Leicester. A Gujarati jago celebration in Birmingham unfolds differently than one in Manchester. The same Bengali gaye holud we photograph in East London transforms when families celebrate it in Coventry. Same tradition, different location, completely different expression.

After years photographing South Asian weddings across the UK—from Hindu celebrations in Leicester to Pakistani events in Bradford, Sikh ceremonies in Southall to Bangladeshi weddings in Tower Hamlets—we've noticed something fascinating: pre-wedding traditions don't just cross borders from South Asia to Britain. They evolve, adapt, and transform based on which UK city, which community, which generation is celebrating.

These regional variations within Britain create photography challenges and opportunities that nobody talks about. Because understanding how a Punjabi mehndi in Slough differs from one in Glasgow isn't just cultural knowledge—it's essential to documenting these celebrations authentically.

Why Location Changes Everything

South Asian communities in the UK aren't homogeneous. They're concentrated in specific cities, built around particular migration patterns, shaped by decades of distinct local development. The Gujarati community in Leicester evolved differently than the one in Harrow. The Pakistani presence in Birmingham has its own character compared to Bradford or Manchester. Bengali communities in East London versus Birmingham versus Oldham—all different.

These differences show up most visibly during pre-wedding celebrations. A haldi ceremony—the turmeric ritual before Hindu or Sikh weddings—happens everywhere, but how it happens varies enormously.

In Harrow, where substantial Gujarati Hindu populations settled decades ago, haldi ceremonies often happen in garden venues or hired halls. They're elaborate, with professional decorations, coordinated outfits, sometimes catering. The ceremony itself maintains traditional elements but feels produced, organised around the expectation that extended community will attend.

In Leicester, with one of the UK's largest Hindu populations, haldi tends towards more intimate family affairs. Back gardens of terraced houses, relatives sitting on sheets spread on grass, turmeric paste made that morning by grandmothers using family recipes. Less production, more tradition.

Same ritual, radically different expression based solely on which UK city you're in. As wedding photographers, we approach these differently—the Harrow version needs documentation that captures the scale and organisation, whilst Leicester celebrations require intimacy and closeness to show the traditional, family-centred approach.

The Jago That Travels

Jago—the Punjabi Sikh pre-wedding celebration involving singing and dancing through streets at night—presents fascinating regional variations. In Birmingham, where Sikh communities are substantial and geographically concentrated, jago processions can be significant events. Streets get temporarily closed, dozens of family members participate, neighbours expect the noise and celebration.

We've photographed Birmingham jago celebrations that stretch across multiple streets, involving portable music systems, elaborate decorations carried through neighbourhoods, genuine street celebration that feels culturally embedded in the local community.

The same tradition in Manchester, where Sikh populations are smaller and more dispersed, looks completely different. Jago might happen in community centre car parks rather than residential streets. The procession is shorter, more contained, adapted to spaces where you're less likely to have entirely Sikh neighbourhoods accepting of late-night celebration noise.

In Southall—with one of the UK's largest Sikh populations—jago returns to something more substantial, sometimes rivalling what you'd see in Punjab itself. The community density supports traditional expression in ways that more dispersed populations can't replicate.

Photographing these variations requires understanding what's possible in each location. In Birmingham, we're documenting street celebration, community participation, the intersection of traditional Sikh ritual with British urban space. In Manchester, we're capturing adaptation, the way traditions transform when communities are smaller. In Southall, we're photographing tradition maintained at almost diasporic origin-level intensity.

Bengali Gaye Holud: Tower Hamlets vs Birmingham

Gaye holud—the Bengali version of turmeric ceremonies—shifts dramatically between UK cities. In Tower Hamlets, where the UK's largest Bangladeshi community is concentrated, gaye holud happens with certain expectations around scale, venue, cultural elements that the community size supports.

We've photographed Tower Hamlets gaye holud celebrations in dedicated Bengali wedding venues, with traditional music, food, and decorations readily available because the community infrastructure exists to support them. Extended family and community members attend because they live nearby, creating the critical mass that traditional celebration requires.

The same ceremony in Birmingham or Manchester, where Bangladeshi communities are smaller, adapts differently. Families might combine gaye holud with mehndi elements from broader South Asian tradition, hire venues that aren't specifically Bengali, incorporate British Asian fusion elements because the community size doesn't support maintaining purely traditional approaches.

In Oldham or Bradford, where some Bangladeshi communities exist but are smaller still, we've seen gaye holud ceremonies that are primarily family-only, stripped to essential ritual elements, celebrated in homes rather than venues because that's what the community size allows.

These aren't failures of tradition. They're adaptations to demographic reality. And photographing them requires understanding what each variation represents—not deviation from an "authentic" version, but authentic expression within specific UK community contexts.

The Mehndi Night Evolution

Mehndi celebrations—pre-wedding henna application events—vary wildly across UK cities, religions, and regions. Hindu mehndi in Leicester tends towards elaborate, music-filled celebrations in hired venues. Muslim mehndi in Bradford or Birmingham often maintains more traditional, intimate, gender-separated approaches. Sikh families in Southall might combine mehndi with sangeet elements in ways that blend traditions.

In Harrow and Wembley, where mixed South Asian populations interact extensively, we've seen mehndi celebrations that blur religious and regional lines. Gujarati Muslim families incorporating elements usually associated with Hindu celebrations. Punjabi Hindu families adopting Sikh sangeet traditions. Cross-pollination that happens when communities share space.

Manchester mehndi celebrations often feel more British-Asian hybrid—incorporating DJs, contemporary music, Western elements alongside traditional henna. The community's slightly smaller size and more integration with broader British culture shows up in how celebrations are structured.

London mehndi nights, particularly in Southall or Wembley, can be extraordinarily elaborate—professional mehndi artists, coordinated outfits, substantial guest lists, events that last late into the night. The population density and wealth concentration allow for production scale that smaller cities can't match.

As photographers moving between these cities, we're constantly adjusting our approach. Large-scale London events need coverage that captures production value and scale. Intimate family mehndi in smaller cities requires closer, more personal documentation. Each variation tells different stories about how South Asian traditions exist in contemporary Britain.

When Traditions Collide and Combine

One of the most interesting phenomena we've observed: traditions combining across religious and regional lines when South Asian communities share British cities. In Leicester, where Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh populations all have substantial presence, we've photographed weddings where families borrow elements from each other's traditions.

A Hindu family incorporating jago-style procession elements usually associated with Sikh weddings. A Muslim family having a haldi ceremony typically considered a Hindu tradition. These aren't cultural confusion—they're deliberate choices by British Asian families creating hybrid traditions that feel right to them.

In Birmingham, we've documented Pakistani Muslim weddings featuring mehndi celebrations structured more like Punjabi Hindu sangeets—with DJs, choreographed dances, elaborate decorations typically associated with different religious traditions. The families aren't abandoning their Muslim identity; they're expressing it through British Asian cultural forms that transcend their religious origin.

This happens less in cities with more segregated South Asian communities. In areas where one ethnicity or religion dominates, traditions tend to maintain more distinct boundaries. But in truly mixed South Asian cities, we're watching new British Asian traditions emerge that future generations might not recognise as combinations.

Photographing these hybrid celebrations requires understanding what's being combined and why. It's not our place to judge whether these combinations are "authentic"—they're authentic to the British Asian experience, which is the only authenticity that matters.

The Second-Generation Effect

How traditions are expressed increasingly depends on whether weddings are planned by first-generation immigrants or their British-born children and grandchildren. This generational difference shows up everywhere but varies by city based on community age.

In cities where South Asian communities are older and more established—like Leicester or Southall—you see more multi-generational influence, with traditions being negotiated between grandparents who remember celebrating in South Asia, parents who celebrated in 1980s-90s Britain, and couples navigating 2020s realities.

In cities where South Asian populations are newer or smaller, second-generation influence is more pronounced. Couples might maintain certain ritual elements because elders insist, but structure celebrations around British expectations—reasonable timings, accommodating non-South Asian friends, venues that aren't community-specific.

We've photographed haldi ceremonies in Bradford that finish by 8 PM because the venue has noise restrictions. The same ceremony in a Leicester family home might run until midnight because the community context allows it. Both are British Asian haldi celebrations, but they exist within different constraints.

The photography challenge: understanding which constraints are shaping each celebration. When timing is truncated, we need to work faster. When space is limited, we adapt our coverage. When traditions are being negotiated between generations, we document both the ritual elements elders care about and the contemporary adaptations younger generations prioritise.

Photographing Regional Specificity

Our approach changes based on where we're working. In Leicester, where South Asian weddings happen constantly and communities are substantial, we can expect certain infrastructures—vendors who understand traditions, venues familiar with specific cultural needs, communities knowledgeable about ceremonies.

In smaller cities or areas where South Asian populations are less concentrated, we're often explaining to venues why we need certain accommodations, working with couples navigating spaces that aren't designed for their cultural celebrations, documenting the adaptation required when community infrastructure doesn't exist.

The photographs that result look different too. Leicester celebrations photograph with a certain embeddedness—traditions happening in contexts that fully support them. Manchester or Newcastle celebrations might photograph with more visible adaptation—traditions maintained but clearly existing within less specifically supportive environments.

Neither is better or worse. They're different expressions of being South Asian in Britain, shaped by local demographics, community history, and the particular evolution of diaspora in different UK cities.

What This Means for Documentary Photography

As documentary wedding photographers, our commitment is capturing what actually exists rather than imposing expectations about what "should" exist. This requires understanding that a "proper" haldi or jago or gaye holud isn't defined by South Asian origin practices but by what British South Asian communities are actually doing.

When we photograph weddings across Birmingham, Leicester, Manchester, London, Bradford, and beyond, we're documenting traditions in evolution. Pre-wedding celebrations that look different in different cities aren't deviation from authenticity—they're authentic to their specific British context.

This regional variation makes comprehensive documentation more complex but infinitely more interesting. Every city, every community, every generation contributes to how South Asian traditions are expressed in Britain. And all of these expressions deserve honest photography that shows them as they are, not as someone thinks they should be.

At Mirage Photos UK, we bring this regional understanding to every wedding. Whether it's a haldi in Harrow, a jago in Birmingham, a gaye holud in Tower Hamlets, or any pre-wedding celebration across the UK, we understand that location shapes expression, that British context changes traditions, and that our job is documenting these evolutions honestly.

Because South Asian traditions in Britain aren't static transplants from the subcontinent. They're living, evolving practices shaped by which UK city you're in, which generation is celebrating, which community is gathering, and how diaspora life adapts heritage to new contexts.

That complexity deserves photography that understands it. That's what we provide.